“Add to that, many (such as myself) have spent years as chefs in quality establishments and you have a paired knowledge of food presentation and photography techniques.”

Read MoreWhy Hire a Professional Food Photographer?

“Add to that, many (such as myself) have spent years as chefs in quality establishments and you have a paired knowledge of food presentation and photography techniques.”

Read More

Weddell seals enjoying the sun.

A couple of weeks ago I was asked if I would like to join scientists James Black and Glen Johnstone for a trip on to the sea ice to help collect samples for their research on ocean acidification. This particular trip was somewhat special in that we also had two journalists from the Huffington Post tagging along to gather content for their upcoming stories! Not only would I be getting off station, but taking a ride in one of the Hagglunds on to the sea ice! Due to the nature of their research, James and Glen are the only people on station permitted to actually do this, as there have been incidents in the past where Hagglunds have fallen through the ice. Luckily they float! This was a great chance to get involved, see more of Antarctica and give the camera a good work out. Needless to say, I was pretty excited. A rare opportunity, especially for the station chef!

Green Hagg covered in ice.

I got up at 5am to get myself organised, make sure my survival pack was in order and sign out a big Down jacket as we would be stationary in the field for quite some time. Just before we left, we packed some lunch, filled our thermos’ with coffee and turned our tags on the muster board to say where we were going, for how long we would be gone and who was in the party. Communications also needed to be notified of the above information with scheduled radio checks every hour. With all of these boxes ticked we gassed up and in two bright coloured Hagglunds headed out of station and off towards O’Briens Bay where the day’s activities would take place. Driving in the Hagglunds is an experience in itself. Everyone inside wears a head set, much like that of a helicopter, as the noise from the engines is deafening. This allows internal communication as well as with other vehicles and the station. I couldn’t help thinking that this must be what driving a tank is like. The grinding rumble of the engines and tracks as we carved a path over a previous trail covered up by the severe, ever changing Antarctic weather. Haggs are fitted out with radar and GPS for driving in whiteout conditions and are amphibious vehicles designed as troop carriers for the Swedish Army. They can go anywhere and that is why we have them.

Glen gassing up before we left station.

It took us about forty-five minutes to reach O’Briens Bay after stopping a couple of times for the Huffington Post journalists to get some shots. We descended to the sea ice and halted before embarking to go through a briefing from Glen as to procedures whilst operating out there. The main thing to take from this briefing was to keep our eyes and ears pealed and if you saw the scientists running, run with them; that means the sea ice is breaking up! However, the ice was 2.8 metres thick here, far more than is needed to hold the weight of a Hagglund. In fact, Haggs can safely drive on ice that is 60cm thick so there isn’t much danger.

After the briefing, the journailsts parked Yellow Hagg on the edge of the sea ice to film whilst we took Green Hagg out to the sites that Glen and James had drilled on past expeditions. The holes were just covered in snow and after the gear was unpacked needed to be scooped off with a chinois from the kitchen, revealing a tunnel 2.8 metres deep to the dark crystal-clear water beneath. I was told that visibility is near to 100 metres under the ice. Lack of current and constant shelter from above means the ocean floor remains undisturbed all year round. This was why it had been chosen as the place to collect the samples that James needs.

O'Briens Bay. The holes can be seen on the ice marked the distinct mounds with poles in them. The drill to make them sitting on a platform off the ice.

James Black, PHD Candidate at IMAS (Institute or Marine and Antarctic Studies) and leading scientist on this project, is one of many scientists around the planet studying Ocean acidification, which is essentially how the ocean is reacting to the increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Black aims to increase physiological understanding of the effects of ocean acidification on phytoplankton and macro-invertebrates. Carbon dissolves into seawater lowering the pH which makes the water more acidic and affects the ability of marine organisms to form shells and other hard structures. In simple terms, animals relying on calcium carbonate for their shells are becoming worse off than plants which are experiencing higher growth from increased photosynthesis, thus the eco system and food chains could change in the future. Also, the Southern Ocean absorbs 40% of the global uptake of CO2, as cold water can absorb faster than warm water, hence why this study takes place in Antarctica.

James Black preparing the ROV.

On this day, we were taking samples of Diatoms (single cell micro algae), from the seafloor to be analysed later in the labs. They will eventually be packed up and shipped to Hobart, where the Australian Antarctic Division’s headquarters are for further analysis and lengthy study. Gear unpacked, James started to organise the ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle), which is to be sent down through the hole to vacuum up samples from the sea floor. The Huffington Post guys are filming and interviewing and I am busy soaking in the surrounds, taking loads of photos and buzzing off the rarity of this experience.

Soon everything was set up and James, Glen and I got to work. The ROV was dropped down the hole with James driving it from a control panel - a black rubbish bag over his head so that he could see the screen projecting real time footage from under the ice. Glen and I man the hose and pump. After a while we see a brown-green colour start coming up through the clear hoses connected to the vacuum, letting us know that we have some samples. The samples are pumped in to a plastic box of sea water and ocean sediment which is kept in the dark so as not to be effected by the sunlight, then buried in snow for when it is time to head back. After about an hour of taking samples we were having a break and standing around chatting when Glen looked over my shoulder with a surprised look… a Weddell Seal had just popped its head up, seen us and shot back down. A few minutes later it reappeared busting out of one of the covered holes fifty metres away! It was a big female and Glen thought, judging by her plumpness, that she was probably pregnant. The seal made a show of rolling around in the snow and doing a few poses for us before a couple of big yawns and slumping into what looks like a blissful nap. I was reminded of a happily overweight person lazing at the beach after a few too many Coronas. She looked as though she was in heaven, and as we get back to our work we could still hear her heavy breaths. The afternoon stretched on with the wind dropping off and the temperature rising. We took off our jackets and were working in fleeces and thermals, carefully applying sunscreen as not to be burnt from the scolding reflection off the ice. Having everything they needed, the Huffington Post guys departed with their escort leaving James, Glen and I to continue on for another couple of hours of sample taking. Later, a second seal popped out of the hole to slide up next to her pal, which we took a few photos of on a coffee break before finally finishing up for the day around 5pm.

Weddell seal yawning.

By the end of the day I was shattered. We packed the equipment away and piled in to the Hagg, said good-bye to our blubbery friends and departed the bay. Somehow throughout the day we managed to polish off three boxes of Shapes biscuits, which I’m told is not unusual as they are practically the the standard field ration for these guys. A quick radio check to comms to let them know we were off the sea ice and it was on the bumpy trail back to station, just in time for dinner and a couple of beers.

Day 10. Survival Training

The Last few days have seen some heavy weather with a temperature of about -1 to -6 and wind chills to -13. The station went to condition red for awhile on Sunday when blizzard conditions came in and visibility dropped to below ten metres. Monday was scheduled for our survival training so those of us pencilled in were hoping the wind would ease and that we would be allowed to head out on the ice. Monday morning was still at condition Yellow but we started our theory practise anyway as the weather was supposed to lighten by the afternoon.

With an early start we had briefings until after lunch, beginning with pre-departure procedures in the red shed and covering everything from map and GPS reading to field safety, gear checks and communications. By mid afternoon the wind had dropped enough for our FTO (field training officer) to give the good news and as a group we loaded up and started our trek to Shirley Island.

Although the conditions had turned to green we were still battling high winds and biting cold temperatures and had to make sure not a single piece of skin was showing. You knew if it was as the cold would sting like a needle and you could easily get frost nip which could lead to frost bite. We left station limits with a quick radio check and about 20 minutes later descended to the sea ice. On our way down our FTO stopped us at a bright orange cache containing a drill kit which he explained we would need to measure the depth of the sea ice to monitor the thaw and make sure it was a safe thickness for us to cross. Once on the ice, a parcel of curious Adelie penguins came awkwardly waddling over to see what these giant yellow beasts were. They only stopped long enough to decide that we were in fact not penguins and therefore not worth any interest before shooting off to join their colony.

Half way across the sea ice we broke out the drill and took turns driving it down until we reached the depth where it broke through to the water below.. The final measurement was 160cm, enough to carry the stations heaviest field vehicles and of no risk to us on foot. As we ventured across the ice to Shirley Island we would prod the ground with our ice axes and walking poles to ensure there we no major fractures for us to fall in to. Often there would be long cracks with a soft top layer that would crumble away when pressure was applied. Still no risk to us but a sure warning that the sea ice was not permanent and would disappear with the coming summer.

Soon we were over the ice and on Shirley island, home to several Adelie penguin colonies. The Penguins are currently in nesting mode getting ready to breed so the maximum distance we could approach was 15 metres unless they came to us. We spent a good while hanging around and taking photos of these curious birds, elated by simply being in their presence. Just watching them waddle about, wings flapping, hopping up rocks and sliding on their bellies, is enough to warm the soul. After a generous break our FTO called the group and we started back across the sea ice and up the hill towards Casey.

As we climbed the hill, a few Adelies from a different colony had seen us and came zipping over. They followed us for quite awhile up the hill but eventually, their curiosity satisfied, concluded that again we really weren’t that interesting. At the top of the hill, with the weather starting to turn, we went through an emergency scenario as to what we would do if one of the group had broken his leg. The winds were picking up and we needed to find the best shelter possible after which we talked about how best alert help, apply first aid and bunker down. The trip back to Casey station became more difficult as we walked in to the head wind which had picked up substantially and visibility had lowered to perhaps 20 metres. Keeping the group tight we pushed on until we came back to station limits, the coloured buildings slowly materialising through the blanket of white.

We made our way back to the field store where our FTO explained our next activity, building dug outs to “bivie" in the snow over night. Luckily for us the weather again turned and the wind dropped right off in time for dinner. We spent an hour building our dug outs and field kitchen before helping ourselves to dehydrated army field rations and turning in for the night. I say night but the sun doesn’t really set. It is light all night. Tucked down in our bivies and sleeping bags I used my neck warmer to cover my eyes and simulate darkness, sleeping surprisingly well and only waking when the condensation in my bag turned to ice. I’d pop my head out for a minute or two for fresh air to be touched by the falling snow before ducking back into my warm cocoon.

Having “survived” the night our group is ticked off on survival training and are allowed to leave station limits to make the most of the recreational areas close to station. The next element of our training will be the Field Travel training where we will learn to utilise the various vehicles at the AADs disposal, thus extending our opportunities to get further into the field. Having only been here for ten days and I can already say I am in love with this continent and can not wait for the adventures ahead.

Marco our Estonian dump boat diver.

My experience with the Pearling industry started at sea and ended on an active pearl farm in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. At the beginning of 2015 I was in Perth after working on the fringe festival for a month. I was trying to decide what to do next, having just concluded not to renew my contract in Arnhemland, NT. Searching the Internet for something adventurous and out of the ordinary, I saw a job advertised as a cook on a pearling vessel. Ever since becoming a chef and perhaps even before that I have dreamt of working at sea. I always saw it as a super yacht or something flash but this was something completely different. I had no idea what “pearling” even entailed. The thought of joining a bunch of pirates on a working ship was enthralling. I passed the phone interview and down to last my last pennies, used my nearly maxed out credit card to book a one-way ticket to Darwin. It was a total gamble, as I was uncertain if I would pass the rigorous medical, drug and alcohol test before I would be signed on. If I failed that I would have been stuck in Darwin with no job and no money. As it turned out, I got the green light and was signed on to work on a gorgeous thirty three-metre sea goddess called the Nalena Bay.

By far the sharpest ship in the fleet, the Nalena Bay held eight or nine pearl divers, two deck hands, two dump boat divers, one engineer, one cook, one domestic and the skipper. Her three decks consisted of the divers quarters on the lower deck below the water mark where most of the crew shared cabins, the engineers quarters, galley, food storage and work deck in the middle. The Skipper’s, dump crew and cook’s cabin along with a tv room were on the top deck. My galley had an adequate kitchen and the walk in chillers and freezer were far beyond my expectations. We could carry a huge amount of frozen stock and while the majority of the chiller was filled with fresh produce, a couple of shelves were kept free for the beer. The rules of the boat were mid strength only and no drinking when steaming. At the end of the day the divers and crew would sit around the back deck under florescent lights to drink, smoke and shoot the breeze before turning in for the night.

These boys work hard for their money and it was my job to keep them gassed up. They do nine fifty minute dives per day to a maximum depth of thirty metres with rapid descents, slow ascents and a break of no more than 20 mins between dives. When they hit the bottom they are carrying a netted sack around their necks, which is filled as they dive and a bigger net hooked to a line to fill with their collected shell. The drogue* floats out the back to create drag and control the boats speed against the tide as the divers are pulled along the bottom of the ocean by long ropes weighed down with massive sinker weights. They are not attached to the rope but use it as a guide down their “line” which is the position they are designated along the booms hanging out the side of the boat. Using entirely their strength and endurance they swim and pull themselves down their line venturing off as needed, in search of the precious oyster shells required by the farms to produce cultured pearls. After they surface from a dive these pirates of the deep pull off their masks and still in their wetsuits, join the rest of the crew at the chipping table to clean their catch of barnacles and impurities. The shell is then loaded into panels and sent via the dump boat out to lines suspended in the ocean by buoys to await collection later and be taken to the farms. Every second dive after the divers have completed their clean they have five to ten minutes to inhale a substantial feed that I would prepare before donning their stinger masks and queuing up to head back to the ocean floor.

We would spend anything from 7-10 days a time at sea, fishing on the neap tides* and spending our springs* back in the town of Broome where we would stay in backpackers or hotels and spend our bounty on all manors of debauchery. Time off was dedicated to lounging about on the pristine Cable Beach for days at a time, watching camels stroll by, the tide rise and fall and evening bonfires soaked in wine and rum. Sail day would see a gang of men and our female domestic, normally hungover and sometimes straight from a hard night partying without sleep arrive at the yard ready to take the short ride out to the storm moorings to board our ship and head back to sea.

Our first journey was from the Paspaley* shipyard in Darwin to Broome around the entirety of the Kimberly, a region where the water temperature is often warmer than the air at around 30 degrees. We cruised the coast past crumbling cliffs of red rock and steamed through the huge archipelago of brilliant green-blues and reds. The skies were by far the most magical I have ever seen. Stars from horizon to horizon, Sunrises and sunsets with every shade of red, gold and purple, and at one point we spent nearly the whole night sailing through an electrical storm. I was out the back of the boat hanging on to ropes and rails with one hand as it pitched and rolled while trying to take photos with the other. Waves ploughing over the deck and sweeping off the side while 360 degrees around us huge bolts of forked lightening were blasting into the ocean. For me it was Mecca. My first real storm at sea! I felt like some adventurer from tales pioneering new lands! The rest of the crew were really not that interested. Most being veterans from years at sea, this was nothing new to them and they were for the most part hanging about the galley chatting or catching some sleep in their cabins below deck.

Another aspect that I thoroughly enjoyed was the interaction with ocean wild life I got to experience. When moored in Roebuck Bay, Broome, we would have scores of Snubfin Dolphin swimming around the boat. It has recently been discovered that the Snubfin Dolphin are entirely unique to that particular bay in Broome. The Roebuck Bay Working Group is a scientific research group that continues to produce information and monitor the species. If the ships lights were left on when we were anchored at sea it would attract all manor of sea creatures from fish to squid, sharks and dolphins. Often there would be dozens if not hundreds of dolphins swimming and playing around the ship. They would play catch with other fish, spitting them high into the air and catching them, jump high out of the water, doing flips and chasing each other around the boat. You would also see the mature dolphins teaching and playing with their young as tiny baby dolphins followed their parents about. The divers sleeping below deck would complain of the chatter they would make, as it would sometimes keep them from sleeping. I would sit out under the stars for hours watching them, being swept away in their innocent playfulness. I truly felt so close to nature in these times and now as I type this in my chalet in the snow-covered mountains my heart yearns for the ocean. As our ship sailed we would often pick up hitchhikers as tired sea birds and land birds that had lost their way would come to rest. There was one particular species of bird called the Storm Petrel that would litter our work decks as they sought shelter in the night. I would be up early and often use a towel to pick up two or three and take them to the fly bridge where they wouldn’t be in the way of the crew as they prepared for their first dives.

The ocean also presents a very real danger to those seeking wealth from her. The diving season starts just after the wet season has finished and there are Irukandji*(sp?) and Box Jellyfish in the water. Although precautions are taken with stinger suits and special masks there would always be some that get through and during my time there were in excess of dozen stings across the fleet. We had two on our boat with one of our crew being stung so badly that he was put on oxygen and morphine and was on watch from the skipper until the toxins wore off. I remember going to check on him and seeing him in excruciating pain rocking back and forth, tears streaming out of his eyes and running down the oxy mask. The Irukandji sting is said to give the victim the sense of impending doom and our diver told me after that he thought he was going to die. Scary stuff! Tiger sharks would be regularly spotted hanging around the divers. Our Head Diver was once startled when one snuck up on him. He turned and without thinking, punched it in the nose giving it a shock and sending it on its way. Also I just missed out on the whale season where the divers would be at risk from curious hump back whales interfering with their work. I heard stories after I left of the whales coming in too close, tangling and ripping out the oxygen lines of the divers who would then have to activate their bail out tank, a small tank clipped to their kit for emergencies only.

As a chef I was spoilt with ingredients. There seemed to be an unlimited budget at my disposal and the boys got what ever they wanted. I would order in lamb racks, beef eye fillet, smoked salmon, croissants and about twenty different ice creams, to say the least. The divers would often haul up seafood from the bottom such as painted crayfish* and other shellfish. Our dump boat diver, a guy named Squid, was a sniper with the spear gun and would keep me well stocked with fresh Tuna, Spanish mackerel and Coral trout. Sashimi* and Ceviche* were a daily smoko*. Nothing was wasted as the crew ate for a battalion, burning it off under water as they worked. My day would start at five am by preparing breakfast and I would be lucky to get a couple of hours break through out the day until I finished my shift at about eight pm. For an hour each afternoon, weather permitting, I would take myself up to the fly bridge and roll out my yoga mat for a half hour of stretching followed by another half hour sitting in my hammock reading in the sun. It was a good life.

My experience with Paspaley is without a doubt one the highlights of my life and has increased my appreciation and respect for the ocean and its inhabitants. Working at sea is definitely not for the faint hearted. You need to be strong minded and ready to work every waking hour. However the camaraderie, adventure and financial benefits are more than compensation. I would do it again in a heartbeat and often regretted leaving the boat. After four months working and living aboard the Nalena Bay I chose to leave and heed the call of a friend in need. Coincidently my friend was working on an active pearl farm in Cape Leveque called Cygnet Bay, and was in serious need of a head chef. Thus began my second chapter within the pearling industry...

*Neap tide- a tide that occurs when the difference between high and low tide is least. Neap tide comes twice a month, in the first and third quarters of the moon.

*Spring tide- A tide that occurs when the difference between high and low tide is greatest. Spring tides come twice a month, approximately at the full and new moon.

*Drogue- a drogue is usually constructed to provide substantial resistance when dragged through the water, and is trailed behind the vessel.

*Paspaley– the largest and oldest Pearling Company in Australia

*Irukandji- are the smallest and most venomous box jellyfish in the world

*Painted Crayfish - are a large edible spiny lobster

*Sashimi- a Japanese delicacy of fresh, raw fish sliced into thin pieces.

*Ceviche- is a seafood dish popular in the coastal regions of Latin America. The dish is typically made from fresh raw fish cured in citrus juices

*Smoko- A short break for a bite to eat and/or coffee. Often accompanied by a cigarette.

***If pearlers or anyone would like to get in touch about the article please do so by email at info@dominichallphotography.com or via the contact page of this website***

I thought I’d start this blog with a trip I just did with a bunch of people I work with at Lake Ohau Lodge. Ohau is situated in North Otago just 30 minutes outside of a little town called Twizel. Think mountains and lakes! Currently it is the tail end of autumn and the beautiful gold and red leaves are mostly lying on the ground having been stripped from their perches by ferocious mountain winds. Cloud often conceals the peaks but clear skies reveal distant glaciers. Mount Cook is visible from our chalet where we have a fire pit and wood fire oven in the front yard.

The climate varies between pleasant to unbearable depending on what the weather is doing and on this weekend we were lucky to have low cloud and little wind. It made for nice walking conditions up the North Temple Valley where the thirteen of us carried enough food, drink and speakers to have a good shindig into the early hours. Rhona, my partner, carried the camera equipment while I took the role of sherpa and carried our camping gear and food etc.

A scenic two and a half hour walk through mossy bush and rock hopping upstream saw us to a gorgeous riverbed clearing near the top of the valley where we made camp and got the fire going. Soon the drinks were flowing and music easing us into a good hearty night of getting cosy with nature. I took the time to get a couple of twilight shots but the light soon disappeared so I stowed my camera and joined in the fun.

During the night the weather came in and it pissed down with rain, which made any sunrise photos pointless. That gave me an excuse to nurse my hangover for a couple more hours before rising. In the dried up riverbed was now a creek and on the steep cliffs of the valley were running half a dozen waterfalls that were not there the day before. Most of the troop departed early in morning while a few of us stayed and decided to go further up the valley to check out the new falls. You could not see the peaks from the base of the cliffs and it looked as though the water was pouring out of the sky itself. We spent another hour exploring and taking photos before the weather really started to pack in. I would have kept shooting but had forgotten to bring my rain cover for the camera so we headed back, this time down the riverbed along the centre of the valley.

After the climb up the valley, we returned to camp where I used my amazing chef skills to combine Mee Gorang noodles and Magi soup for one last feed before stowing our soaking camping gear and empty bottles into packs. We took our time heading back through the dripping forests and slippery rock beds to the cars and the short drive back to the lodge to curl up in the warmth of our chalet. I am so stoked to have gotten to do this hike as it was the last opportunity before the snow started falling and the winter weather began its crusade. A few more weeks and I'll be up the ski field chasing snowy landscapes.

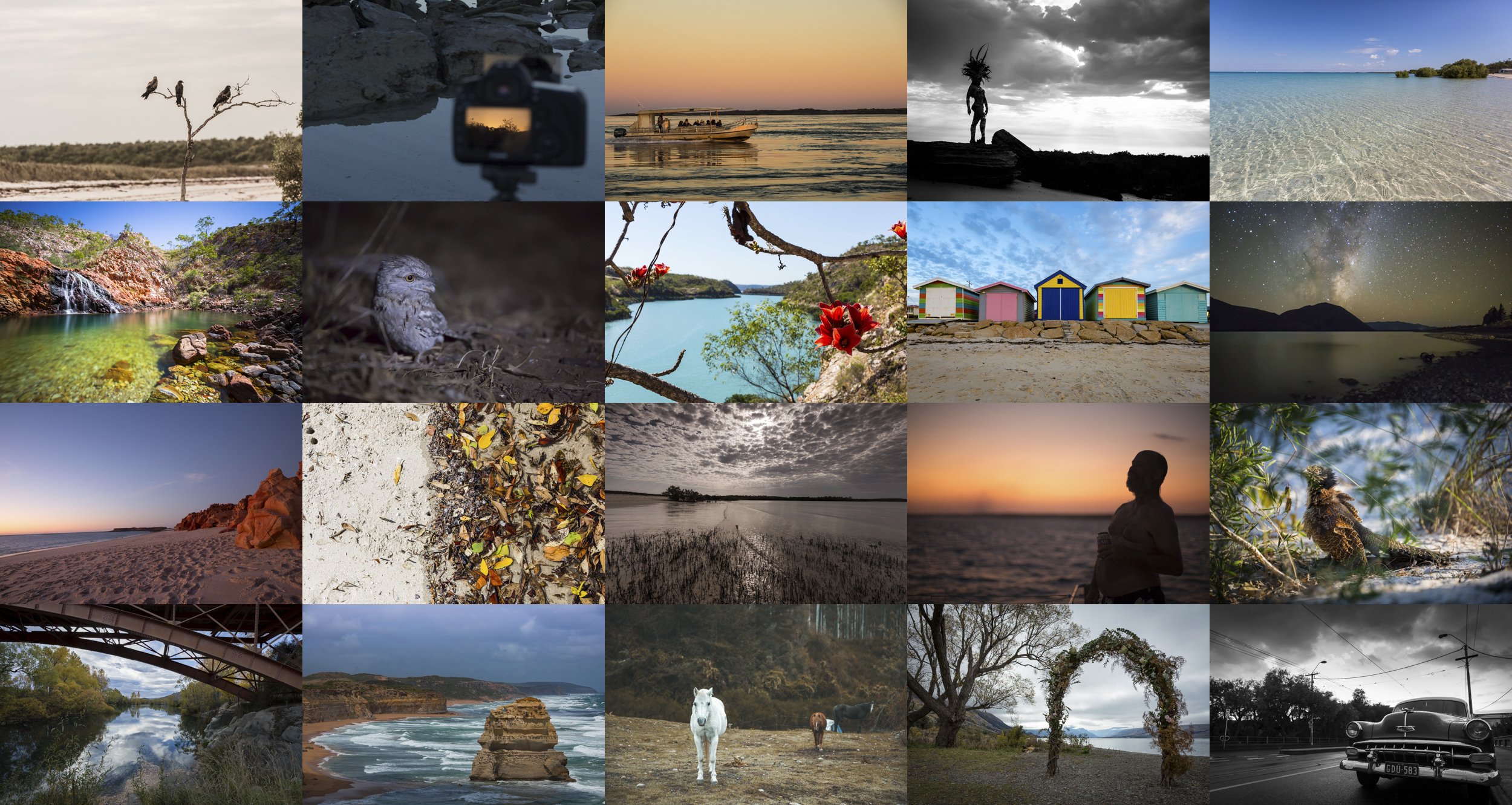

For the last few years I have used my trade as a chef to fund my passion for photography and travel by acquiring work in remote locations around Australia and New Zealand. This lifestyle sees me constantly living out of a suitcase, travelling often and gaining access to areas I could never afford or get permission to visit. Through this blog I’m going to give a visual story telling of some of my experiences. I’m not setting out to give a literary masterpiece but more to tell the stories behind some of the photos and places I’ve visited, and share some great pictures that are sitting dormant on my numerous hard drives. From living in the burning outback of the Northern Territory Australia, to life at sea on a pearl diving vessel, numerous trips to Indonesia and my current state of wintering on a ski field in the South Island of New Zealand. I spent six years working and travelling Australia and have seen more than most Australians have. Now I am dedicating some time to exploring my own country. I have grand plans for the future and would like to invite you to follow my travel and adventures. Please pardon any grammatical error as I did my best to not be present at school and only made it to sixth form English. Anyway here we go…

“Whether to float with the tide, or to swim for a goal. It is a choice we must all make consciously or unconsciously at one time in our lives…. But why not float if you have no goal? That is another question. It is unquestionably better to enjoy the floating than to swim in uncertainty…”

- Hunter S. Thompson

For a long time I had no direction in life and simply cooked at one job until I got bored and found another. Like a lot of people, I stressed that I had no clear path to follow. That is until I came across a letter from Hunter to his friend giving advice on his potential life choices. I almost felt it was written for me and often when I am at a cross roads I will read it for reassurance. After years of blissfully floating I have finally found what was missing and have set sail in pursuit of my dream to be a professional photographer. This is how I have come to accept and give purpose to my nomadic lifestyle whilst shredding the guilt of one who squanders their time and ultimately being at peace with my choices.